Richard Burton was someone I knew well – I liked him drunk and sober. During the filming of Becket, in which he played the martyred medieval priest, he invited me to stay with him for a few days on location in Northumberland. ‘I can promise you plenty of booze, good grub – and my ego to keep you agog,’ he said.

He was at the height of his infamy, post-Cleopatra, and enjoying every minute of it. Everybody knew his name. Every Hollywood producer worth his salt was vying to get his signature on a contract. Fans chased him for his autograph or simply to shake his hand. Pretty girls wanted to sleep with him – though there was nothing new in that.

Julie Andrews, who starred with him in Camelot on Broadway, was his only leading lady with whom he had not slept. He treated her flat refusal to succumb to his charms as a great loss to both of them. He was, admitted one famous and grateful conquest left by the wayside, ‘a man and a half’.

Certainly, he had a terrific way with women. ‘I don’t think he has missed more than half a dozen,’ admired the veteran Hollywood actor Fredric March, who had seen it all. He said Burton made Errol Flynn look like the head of the Cistercian order of monks.

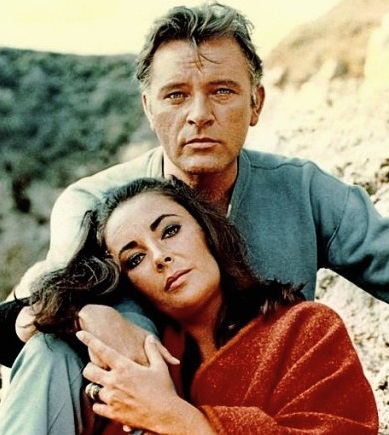

Burton, who died 25 years ago next week, cynically called his notorious relationship with Elizabeth Taylor ‘the Great Roman Dalliance’. It began during the making of Cleopatra, the $40 million epic that broke up their marriages – Taylor’s to the singer Eddie Fisher, Burton’s to Sybil Williams, a former Welsh actress with whom he had two daughters.

The affair had caused the biggest movie scandal since 1921 when, at a wild Hollywood party, Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, one of the greatest stars of the silent screen, fell asleep on top of a starlet named Virginia Rappe and crushed her to death. The public turned against him and his career was finished.

Nobody died in the Burton-Taylor scandal, but the public outcry was as clamorous and pitiless. The scandal turned the spotlight on the Welsh actor like never before. But instead of destroying him – he had been the second choice, after Stephen Boyd, to play Marc Antony – the affair made Burton a superstar.

His face, marked by brandy, fights, and hangovers, was not a film star’s face. But his voice was so rich that one critic said it “could give an air of verse to a recipe for stewed hare.”

Theatre audiences adored him. Only three actors before him—Sir Henry Irving, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, and Sir John Gielgud—had played Hamlet more than 100 times in a single production. Burton joined them, becoming the longest-running Hamlet on Broadway. “I was a sort of Tommy Steele of the Old Vic,” he once said. Winston Churchill called him “my lord Hamlet” whenever they met.

Critics acclaimed him, and fellow actors envied his range. On stage, he was box-office dynamite, but in movies, he struggled. His Hollywood debut in 1952’s My Cousin Rachel was a disappointment, despite a £17,500 paycheck. He fared no better in The Robe, The Rains of Ranchipur, or Alexander the Great. “The Robe was lousy but an almighty hit. I was dull as ditchwater and an almighty flop,” he said.

Cleopatra changed everything, along with his affair with Elizabeth Taylor. Their first encounter didn’t go well. “Richard came on the set and said, ‘Has anybody ever told you that you’re a very pretty girl?’” Taylor recalled. “I thought, Oy gevalt, the great lover, the great wit, the great Welsh intellectual, and he comes out with a corny line like that!”

Elizabeth Taylor recalled their affair’s rocky start: “Richard came on set and said, ‘Has anybody ever told you you’re a very pretty girl?’ I thought, Oy gevalt, the great lover comes out with a corny line like that! But his hands were shaking, and he had the worst hangover. I realized he was human. That was the beginning of our affair.”

Their on-set chemistry was undeniable. Director Joseph Mankiewicz warned the studio: “Liz and Richard are not just playing lovers—they are lovers.”

Despite fears their antics during Cleopatra would ruin their careers, they became Hollywood’s hottest couple. Burton once told Eddie Fisher, “Elizabeth is going to make me a star,” and their next film, The VIPs, was a hit. Burton joked, “If you’re going to make rubbish, be the best rubbish in it.”

Not everyone approved of his Hollywood success. Laurence Olivier warned him about choosing fame over greatness, but Burton embraced it, collecting $500,000 per movie.

Burton and Taylor married in 1964, divorced in 1974, remarried in 1975, and finally separated in 1976. They lived extravagantly, buying a yacht and expensive jewelry. Despite their tumultuous relationship, Burton admitted, “Our love is so furious that we burn each other out.”

After Taylor, Burton married model Suzy Hunt, but it ended in 1982. He quipped, “Divorce is an expensive business. But God put me on this earth to raise sheer hell. And I guess women are part of it.”

Burton’s career declined as he worked harder for less money. Critics noted his dissipation. His fame persisted, but his life was marred by drunken episodes and poor films. He died from a cerebral hemorrhage at 58.

Before his death, Burton, then married to Sally Hay, spoke optimistically about the future despite his health issues. He quoted Keats: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

Despite never winning an Oscar, Burton is remembered for his powerful performances in The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, The Night Of The Iguana, Becket, and The Taming Of The Shrew. He was a rollicking, fascinating, talented friend who drank too much and died too soon.